Ilya and Emilia Kabakov review – Russia’s great escape artists

The Man Who Flew Into Space from His Apartment is based on the communal Moscow flat where Ilya Kabakov once lived. It is a one-room catharsis. All the deprivation endured by millions of Russians through the 20th century is crowned with an exhilarating vision of escape (and a jab at the Soviet space race too). If only it was not so impossible, this collective dream.

Kabakov was born in the former Ukrainian SSR in 1933. He is a poet of a painter, a storyteller of a sculptor and, with his wife, Emilia (born 1945, also in the Ukraine), a pioneer of the total installation. This famous piece, from 1985, grew into a historic masterpiece called Ten Characters, shown when the Kabakovs had managed to emigrate to New York in 1988. Each character had a room in what amounted to two walk-through apartments: the man so short he wanted everybody else to hunch over; the talentless artist who got masses of official work; the tenant who never threw anything away. You can see his cell at Tate Modern, every object labelled and displayed in case he lost the memories associated with a lifetime’s junk, into which he has vanished.

Ilya Kabakov is almost as much a writer as an artist. His characters exist in words too, very often in tense monologues hammered out on old typewriters. Madmen from Gogol, as written by Chekhov. Sometimes these people are artists, or would-be artists, like Sedykh, who sees little white men walking around his apartment night and day. He builds a tall glass cabinet strung with wires, in the hope of enticing them to linger long enough to be seen for more than a moment. He succeeds.

It’s a marvellous sight: strings of tiny figures, some ascending, some descending, like a modernist vision of the afterlife. Other little men appear throughout the show, dotted in corners, or becoming suddenly visible through telescopes in a darkened chamber apparently glowing with planets. Look closely into outer space, however, and what do you see: a parallel universe of crowded Soviet apartments.

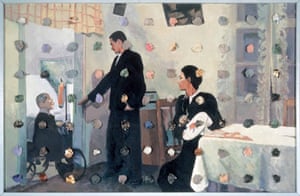

This art is tragicomic, and often mordant. Forced to work under a pseudonym in the 1970s, when his art had become too controversial, Ilya Kabakov began to invent alter egos. Most piquant is the official socialist realist painter commissioned to produce thriving scenes of collective farms and modern high-rise cities. Alas the commission falls through and the canvases decline in storage. Years later, to cheer himself up, the artist tries gluing flowers to the pictures and calling them the Holiday series. But the flowers are just fading sweet wrappers that can’t conceal the banality beneath. The result is absurd and yet sinister too, invoking the fate of the many Soviet painters who fell out of favour.

Kabakov’s own career as a painter fills many rooms of this enormous show, starting with a self-portrait from 1962 in aviator’s headgear, in which one senses both the tribute and the sardonic rebuke to the sky-high aspirations of the Russian avant garde. It’s not long before his painting turns conceptual. A football player kicks a bright yellow suprematist disc into a halcyon blue expanse above the place name “Uglich”, in 1964; Uglich’s hydroelectric plant was built by starving gulag prisoners: art versus reality. In the 70s he paints text-based parodies of party documents and Soviet literature, as well as Masonite works where nameless faces and objects appear buried beneath the surface.

In one work, the objects have broken free. Two builder’s shovels emerge from a realist depiction of a vast construction site. Lettered across the canvas is a long list of all the promised schools and hospitals that will be completed by December 1979. Kabakov’s picture was painted four years later. The shovels are here, and not there; work, by implication, hasn’t even begun.

Lately, Ilya Kabakov has been playing games with paintings that fuse trompe-l’oeil collage with Soviet visual cliche. Too many of these canvases weaken a survey – the Kabakovs’ first in this country – which could have been epochal. And although they are geniuses of theatrical mise-en-scene, there are only four large-scale installations here and none of the Kabakov’s magnificent films.

Still, even their smallest scenarios are potent. Look down, God-like, into the roofless model of a Russian apartment and you see that all the rooms incorporate doorless toilets. So plausible is this miniature reconstruction that people have asked the artists whether it is some sort of ethnographic record, rather than a metaphor: most Russians live in a toilet.

In one cavernous gallery the red tail-lights of a lifesize train give the illusion of departing along tracks disappearing into darkness. We’ve missed the train. Abstract paintings lie shattered along the route, again invoking all those artists purged by Stalin. Soviet horror bleeds into universal nightmare. A glowing sign on the back of the train repeats the show’s title: Not Everyone Will Be Taken Into the Future.

And this train has frightening associations with other crimes against humanity. Ilya Kabakov’s mother was Jewish.

The show’s centrepiece – its soul – is a tribute to this beloved woman in the form of a labyrinthine corridor, hung with nostalgic photographs of Mother Russia alongside typed extracts from her harrowing autobiography. The contrast between landscape and life – the starvation, antisemitism, homelessness, violence and penury she endured – is shattering. The journey through this dim maze, increasingly narrow, is both melancholy and profoundly compelling, until at last you come upon the source of the low requiem that fills the air. Or so you think. For the cramped cell at the heart of this apartment is empty too. All that’s left is an old cleaner’s broom.

Lesen Sie diese interessante Ausstellungsrezension auch auf The Guardian.

Das könnte Sie auch interessieren

Ausstellung Ilya & Emilia Kabakov. Von Zeichnun...

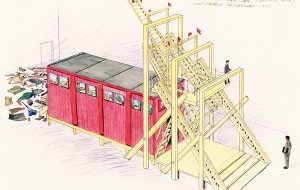

The Red Wagon, 1991, Buntstift, Aquarell, Tusche, 28 × 41 cm © Ilya and Emilia Kabakov Ab dem 17. Oktober...

Ilya & Emilia Kabakov – Ship of Tolerance – Pre...

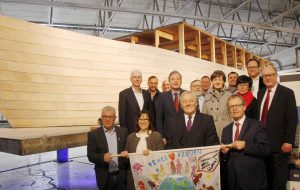

Im Brückenkopfpark Jülich (Kreis Düren) hat das »Ship of Tolerance« von Ilya und Emilia Kabakov seinen ersten...

Projekt des Künstlerehepaares Kabakov macht Station ...

Im Sommer 2019 macht das „Ship of Tolerance“ von Ilya und Emilia Kabakov im Brückenkopfpark in Jülich Station. Bis...

Ilya und Emilia Kabakov – Galerie Breckner bri...

Das Ship of Tolerance, ein weltumspannendes Kunstprojekt des Künstlerehepaares Ilya & Emilia Kabakov, kann durch die...

Kunstverlag Galerie Till Breckner - Editionen. Ausstellungen. Projekte. © 2018-2021, Alle Rechte vorbehalten.